Perched some 10,000 feet above sea level, atop a mountain ridge near Sölden, Austria, is Ice Q, a cubelike glass box that serves as a restaurant, lounge, and meeting space. Overlooking more than 250 alpine peaks, with panoramic vistas of the Italian Dolomites beyond, the annex to the family-owned Das Central hotel stands in stark, modern contrast to the organic beauty all around. But beneath its effortlessly sleek exterior lies a wealth of architectural heft: Innsbruck, Austria–based architect Johann Obermoser met a range of challenges, from structural (Ice Q is entirely built on permafrost, necessitating a stealth network of piles, posts, and plates beneath) to practical (a heat-recovery system and triple-glazed glass make it energy-efficient). Perhaps its most winning endorsement? An appearance in the recent James Bond film, Spectre.

With its lack of superfluous detail, Ice Q makes a strong case that less-is-more design can make an enormous impact, especially in a dramatic natural setting like the one it’s in.

This gleaming beacon isn’t a one-time aberration, either. It’s one of many eye-catching structures that have sprung up in the past few years. Like the starkly sculptural Refuge du Goûter in the French Alps—a shining steel-clad testament to modern design that temptingly awaits as a reward to those who have climbed Mont Blanc. Part of the 52-foot-tall lodge, designed by Swiss architect Hervé Dessimoz, juts out over a nearly 5,000-foot drop. Inside, the egg-shaped superhut is something less than luxurious (think communal quarters with bunk beds), but then guests at Refuge du Goûter have more important things on their minds than the thread count of their linens—the venue is designed to house climbers who can’t make it down the mountain before sunset. (Though the refuge won’t turn away travelers in distress, reservations are required and should be made several months in advance.) The interior is an elegant interplay of form and function, with room for up to 120, and a modern aesthetic built on the constant interplay of steel and light wood.

In the same vein sits the Monte Rosa hut, in Zermatt, Switzerland. You’ll need serious skill—and equipment—to get there: the four-hour hike up to it involves gaining 1,640 feet of altitude, plus passing over a glacier and tackling a 10-story rock wall. But, if you have the skills, the view is worth it. Climbers are treated to a breathtaking Matterhorn view from the striking, almost surreal structure, with its seemingly random window placements and sharp, angular lines. As with Goûter, there are common rooms, each with three to eight bunk beds, and the look is light and airy, with pinewood filling the space.For those who appreciate modern design but aren’t quite ready to sacrifice life and limb to immerse themselves in it, there are plenty of similarly designed hotels dotting the Alps. The Austrian state of Tyrol has a particularly huge concentration of hotels and vacation houses that exemplify the aesthetic. Case in point: Refugio Laudegg, a minimalist structure made even more so by the fact that it’s next door to a 12th-century castle; the Aradira apartments in Kappl, another modern cube-based design that incorporates large windows and local wood and slate; and the five-star Hotel Zhero, in Ischgl, which combines modern architecture with a list of amenities that isn’t quite minimal (think a full-service spa, in-house ski shop, and an award-winning open-grill restaurant from chef Klaus Brunmayr) but is avant-garde throughout.

Then there’s arguably the most futuristic and spectacular of the hotels: the Hotel Arlmont, in St. Anton am Arlberg, which takes modernism’s sleek aesthetic to an extreme without sacrificing practicality at all. A sculptural structure made of concrete poured into a shape that allows for maximum sun exposure in every room (via the expansive floor-to-ceiling glass windows), it has a streamlined style that’s a jaw-dropping antidote to convention—but not out of line with tradition. That’s because many of the area’s hotels incorporate both old-world and modern elements, like Sölden’s Bergland Hotel, where faded, aged (but beautifully so) leather club chairs sit in a lounge that makes liberal use of glass and light wood, and the Giatla Haus, in Innervillgraten, a more-than-300-year-old farmhouse that houses four ultra-modern apartments but hasn’t lost any of its original character, right down to the fact that sheep’s wool is used for insulation.

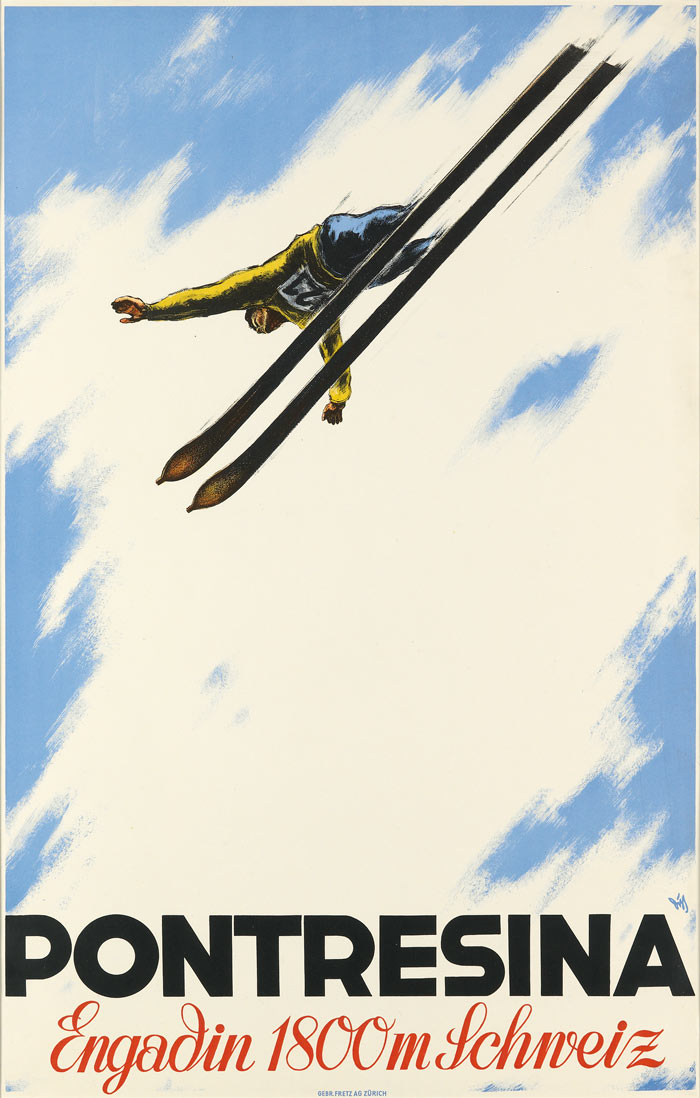

Despite its recent prominence, alpine modernism has been around since the 1920s and ’30s, when minimalist posters—a number of them clearly inspired by Italian futurism—beckoned travelers to the mountains. Underlying the aesthetic was a reverence for the democratizing effects of technology: ski lifts and towropes made skiing accessible for the masses.

The Alps may seem like an odd home for modernism, but looked at another way, the alpine setting, with its beauty and built-in drama, perfectly suits the style. The simplicity of form and the elimination of extraneous detail that define modernism are the perfect complements to the region’s spectacular natural beauty. The same is true for the modernist concept of “truth to materials,” the belief in natural materials and the charge to reveal, rather than conceal, their true nature. It’s also a practical matter—given the challenges presented by the terrain, local materials are often the only ones available.

Finally, there’s modernism’s emphasis on right angles—it’s often 90 degrees or nothing. The resulting look provides a particularly striking counterpoint to the arbitrarily jagged peaks and angles of the Alps, not to mention the pitched-roof wooden houses that dominate the collective memory. The design is set apart, yet cohesive—the perfect stage for sport and style.

- Rudi Wyhlidal

- Swann Auction Galleries

- Courtesy of Ice Q

- Photograph by Rudi Wyhlidal; Courtesy of Ice Q

- Courtesy of Wiki Commons

- “Pontresina” poster by Alex Walter Diggelmann; Courtesy of Swann Galleries