Insider’s Guide: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

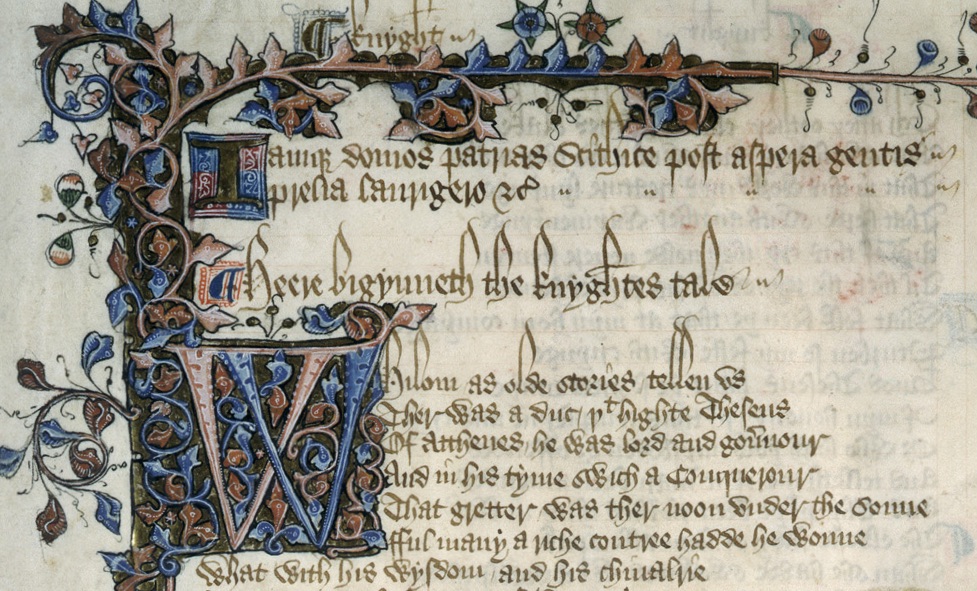

A sprawling estate in San Marino, California, is home to an unparalleled collection of art, literature, and botanical wonders—and Ralph Lauren’s first West Coast runway showA rose with white and pink fringes named Miss Congeniality. A face-to-face encounter with The Blue Boy, the 18th-century portrait of a youth in a fashionable getup by English artist Thomas Gainsborough, once considered one of the most famous paintings in the world. A peek at the Ellesmere Manuscript, a 15th-century handwritten version of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales—one of the earliest transcriptions of the Middle English opus. A peaceful moment resting in the shade of a pagoda by the koi pond in the Chinese Garden.

There isn’t really a wrong way to experience The Huntington, whether you’re there for one of the three core tenets—art, plants, or books and manuscripts—or just to find some inner peace wondering the sprawling, scholarly grounds.

Founded in 1919 and located in San Marino, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens—as it’s properly called—is a 207-acre estate that features 8.8 million manuscripts, 42,000 pieces of artwork, and 16,000 different kinds of plants. When railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington died in 1900, he left his significant wealth to his widow Arabella Huntington and his favorite nephew Henry E. Huntington. Henry purchased the land on which the museum stands now in 1903 and built a mansion, all the while keeping correspondence with Arabella, who had become a collector of art, jewelry, fashion, and furniture.

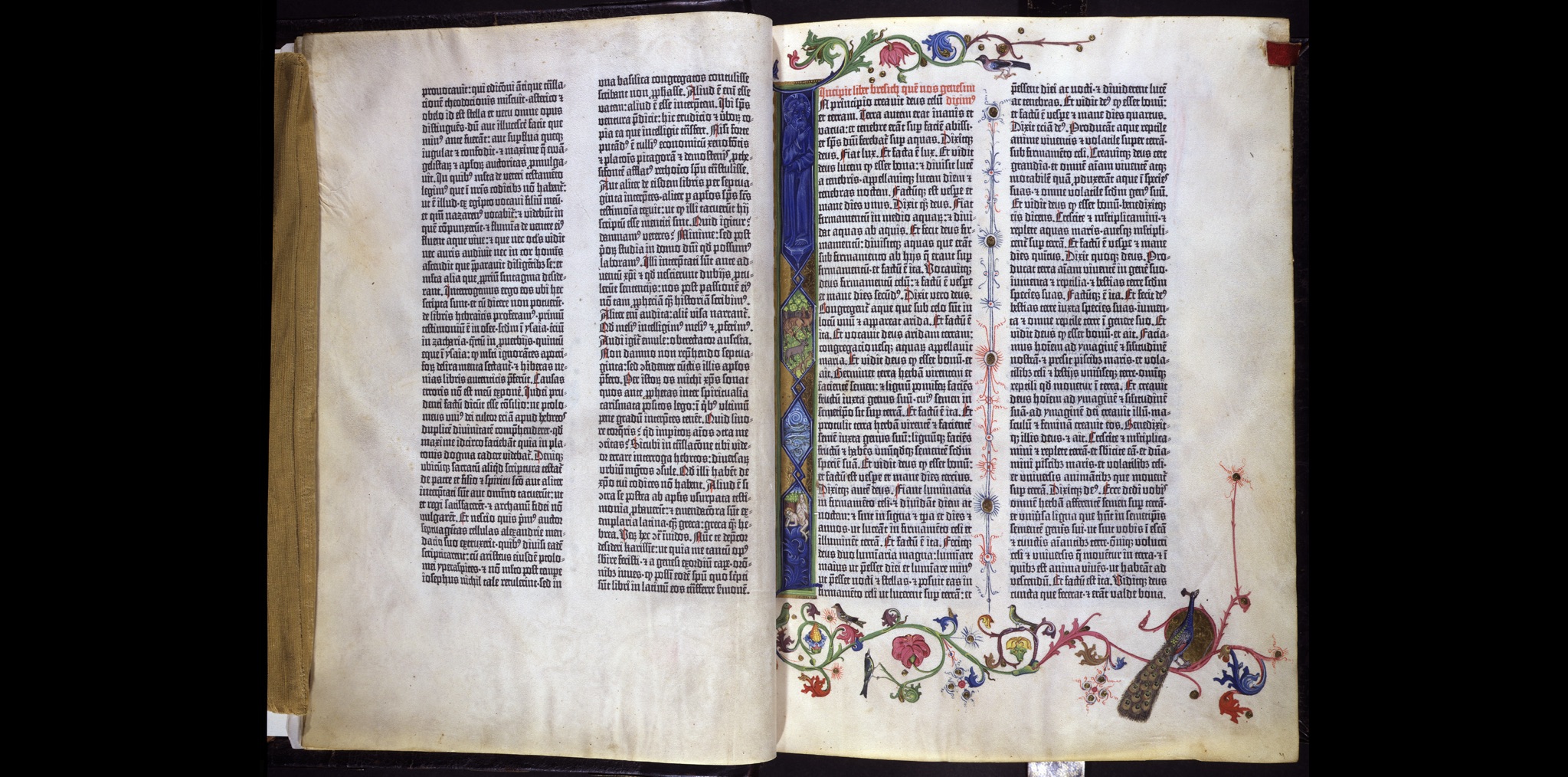

While Arabella was in Paris collecting, Henry was growing his vast riches with his real estate and railroad ventures. He began developing the gardens with the help of renowned landscape architect and horticulturalist William Hertrich. He also began voraciously collecting books, buying entire collections and even purchasing what was, at the time, the most expensive book ever bought: a Gutenberg Bible, which remains one of the library’s biggest attractions. In their continued correspondence, Arabella would encourage Henry to collect art, leading him to start buying up extraordinary European paintings.

In a twist of fate, in 1913, Henry and Arabella would marry, rejoining their fortune and pooling their collections together. By 1919, the estate was endowed as a research and education facility to be opened to the public after their deaths. Arabella died in 1924, Henry three years later, and a year later The Huntington opened. Today, more 800,000 people walk its grounds every year, each experiencing it in their own way.

The Library

Home to millions of manuscripts and hundreds of thousands of books, prints and ephemera, photographs, and digital files, the library is a treasure trove of the written word. The exhibition hall features highlights like The Canterbury Tales and one of 12 surviving vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible from the 1450s, as well as other rarities from the American West and manuscripts by authors like William Blake, Henry David Thoreau, and Jack London. And don’t miss the spectacular hand-painted pages from John James Audubon’s classic book of bird identification, Birds of America.

The library also plays host to scholars and fellows. Caitlin Hartigan, a former fellow at The Huntington in 2014–15, had access to the stacks beyond what the public gets to see. “During my fellowship, I researched the medieval ‘best-seller,’ the Roman de la Rose,” she said. “I was mesmerized by some of the works that I studied, including exquisitely detailed illuminated manuscripts and early printed books with fascinating marginalia. Some books were smaller than the palm of my hand.”

Insider’s Tip: Don’t miss the hand-typed draft (with notes) of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, a science-fiction classic by the late Pasadena-born novelist, who bequeathed her papers and notes to The Huntington upon her passing in 2006. “She was a pioneer, a master storyteller who brought her voice—the voice of a woman of color—to science fiction,” said Natalie Russell, former assistant curator of literary manuscripts at The Huntington, in 2017. “Tired of stories featuring white, male heroes, she developed an alternative narrative from a very personal point of view.”

The Botanical Gardens

Arguably one of the best botanical experiences in the world is the multifaceted botanical gardens. The grounds are split into several large swatches—the Japanese Garden, the Chinese Garden, the Subtropical Garden, the Jungle Garden, the Australian Garden, the Shakespeare Garden, and the Desert Garden among them—and visitors can spend an entire day just wandering around. Most of the plants have placards to identify which one of the thousands of species of flora you’re gazing upon.

The Chinese Garden, known as the Garden of Flowing Fragrance, features a 1.5-acre lake filled with vibrant koi, a teahouse, and even a waterfall, while the Japanese Garden’s Zen garden, bonsai courts, and flowing river are spectacular. Not to be outdone, the Desert Garden is one of the best in the world, says Nicole Cavender, the Telleen/Jorgenson Director of the Botanical Gardens. “Probably our biggest core collection is the succulent collection in the Desert Garden,” Cavender explains. “It’s a must for plant enthusiasts and people who are interested in plant diversity. We have one of the largest desert collections—thousands of species in the cacti family and other families that are drought-tolerant. I call it the ‘convention of desert plants from around the world.’”

The gardens also engage in conservation—The Huntington has an extensive seed bank and exchanges with other botanical gardens across the globe. “We have exotic plants from all over the world,” says Cavender. “It’s meant to showcase the amazing diversity we have on Earth and to help protect it. How do you protect things? Well, you have to understand them first. So we have a great place to study, observe, and really understand these plants. We do exchanges and conservation horticulture, which is figuring out how to reproduce the plant and keep it protected in either a living bank or seed bank, and ideally we would be able to get some of these plants back out into natural population, but that’s getting harder (because of climate change).”

Probably our biggest core collection is the succulent collection in the Desert Garden. It’s meant to showcase the amazing diversity we have on Earth and to help protect it. How do you protect things? Well, you have to understand them first.

Insider’s Tip: “Well I guess it won’t be a secret anymore,” says Cavender about her favorite hidden spot in the gardens. “If you go to the north vista and go off to either side, you have the camellia garden on one side, and on the other side there are a lot of winding paths. You may overlook them if you’re a first-time visitor. There are a lot of paths that meander, and I would advise getting lost there. You can’t really get lost, but that’s a fun shady area—especially if it’s a hot day. There’s even a sculptural bench that took me a long time to find—it’s hidden in plain sight. That’s an area that I recommend people explore more.”

The Museum

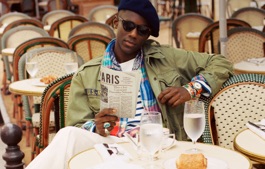

The museum is set in the former home of Henry and Arabella Huntington, so it has a cozy, lived-in feeling that makes it unique. The collection features many pieces of 18th-century British grand manner portraiture, including The Blue Boy (1770), as well as Thomas Lawrence’s Pinkie (1794) and Joshua Reynolds’ Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse (1784). Elsewhere in the gallery are important collections of 19th-century British landscapes, 19th- and 20th-century American art, furniture, and sculptures. One of the most recent acquisitions of the museum is contemporary artist Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of a Young Gentleman (2021), which features a well-dressed young man in the fashion of today—much as The Blue Boy was a reflection of the youthful fashion of 250 years ago. The painting was made in response to The Blue Boy, which Wiley had observed as a child, and which he considers an influence, and it is hung directly across from Gainsborough’s painting.

Insider’s Tip: There are three works by California-based contemporary artist Mineo Mizuno, including Komorebi - light of forest and Thousand Blossoms, which fits so well into the main hallway of the museum that you might miss it on your way to the galleries. The installation is set next to two 17th-century terracotta figurative sculptures representing Flora, the Roman goddess of flowering plants, and a tree nymph—as if under their watch—and includes ceramic dogwood blossoms and an oak stump from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains, where Mizuno lives. Not to be outdone: Outdoors on the museum’s loggia, Mizuno’s work Nest is mean to be taken in with the natural surroundings of The Huntington. The basis of the works are manzanita branches (also sourced in the foothills of the Sierras), which are combined with steel, aluminum, hemp, and ceramic to create nestlike forms that look out onto the grounds of The Huntington and offer a perfect contemplation point.

- Courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens